Having undertaken population forecasts for more than two decades, clients at presentations would often ask me, “What’s the biggest risk with your forecasts”? I would often point to overseas migration at the macro level having a big impact. I might suggest the strength or weakness of an industry-leading to very different population outcomes at the regional level. I might suggest perhaps changes to the planning system, leading to new or more limited opportunities for residential development.

However, if there was a level of dissatisfaction with those comparatively banal answers, the response would be, “A pandemic”. Usually, this response was given in jest but has proven to be the most truthful of answers.

Unexpected outcomes

We have all lived the highs and lows of COVID-19 through 2020 and 2021, and especially the uncertainty and suffering it has brought for some. However, after a year of triumphs and successes, what has emerged that was so unexpected?

Mortality rates

At the macro level, the almost complete closure of international borders in March 2020 has led to comparatively low levels of infection in the community. The impact of high mortality rates from rampant infection in other countries has been largely avoided in Australia. This has been an unexpected surprise and one for which we are all grateful.

For a country that has no memory of a pandemic, we have been ‘forced’ to look at the experience of other countries where infectious disease kills many. We have asked our parents and grandparents what it was like when there was no penicillin or what was the impact of disease such as polio on the community? The spread of the Spanish Flu pandemic one hundred years ago has also provided many clues.

Although outbreaks have occurred, most painfully in Victoria, the virus has not led to many deaths and the initial belief that the propensity for death would be more than 10% has lowered over time to just above 3%. Of course, these rates are much higher in vulnerable communities, especially with elderly persons. Then again, it was also a great surprise that children, who are traditionally more susceptible to infection, have shown greater resistance to picking up the disease and have very low rates of mortality.

The impact has been so limited that few population forecasts for Australia have adjusted the mortality assumptions to account for COVID. In Victoria, where the 2020 outbreak was most serious, the number of deaths has surpassed 800. This is a substantial number, but it likely to represent less than 2% of deaths in the State over a year.

The rollout of the vaccine should provide some greater level of security moving forward, but the questions remain:

• Will it be effective, especially with new strains emerging?

• Will enough people vaccinate to ensure herd immunity?

• Will there be a marked difference in the efficacy of the various vaccines?

Until there is greater clarity around these questions, a truly definitive ‘post-COVID’ outlook for mortality assumptions in Australia remains elusive.

Overseas migration

From the start of my professional career as a demographer and analyst twenty-five years ago, the impact of overseas migration on Australia has grown and flourished. The impacts are profound and multi-faceted on Australian society from the food we eat, the people we marry, the jobs that we undertake and the vast demographic and economic contribution that migration has produced. Overseas migration has increased vastly since the economic downturn of the early to mid-1990s. Overseas migration has greatly enhanced the skill base of the country and brought many younger people into the country’s economic life.

Given the number of persons arriving and departing from Australia on a daily, weekly and monthly basis, it seemed almost inconceivable that the international borders could be closed so comprehensively. Overseas migration had seemingly become the lifeblood of the Australian economy and demography, providing direct employment in tourism and hospitality, stimulating housing markets, bringing money into the economy and helping to renew young adult and child age groups.

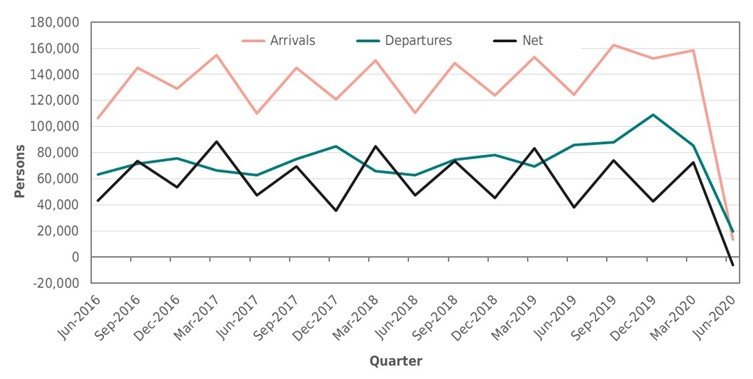

However, in March 2020, the Australian Government ‘turned the tap off’ and since then in-migration flows have reduced to less than 10% of the previous quarter. See chart below.

Net overseas migration flows by quarter, June 2016 – June 2020

Source: ABS, National state and territory population (Cat. No. 3101.0)

What has been so unexpected is that Australia has gone from having a major gain to a loss in overseas migration in the space of months. A net loss in overseas migration has never been recorded in Australia’s history since the ABS started publishing annual/quarterly figures in 1972. It is unlikely that Australia has been in this position since the early years of the second world war (1940 or 1941).

Why is Australia losing population through overseas migration? It seems that the process for arrival here remains more difficult than for those seeking to return overseas. The limited hotel quarantine program and the ongoing risk associated with return travellers means that this situation is unlikely to change in the short term. The numbers may reverse if the outmigration slows, especially in view of the comparatively better health and economic situation in Australia compared to most countries that are struggling to deal with COVID.

Questions about the effectiveness and speed of vaccination programs here and around the world will determine when business as usual can return.

Fertility rates

Fertility rates have been falling in Australia since 2012 and most notably in the last few years. This is a return to the long-term trends that have been prevalent since the 1960s. However, this followed more than a decade of minor gains and stable fertility rates from the early 2000s onwards. The interesting thing is that overall births have remained relatively stable at just on or above 300,000 per annum, due to the increase in persons in the fertile age groups. See chart below.

Fertility rates and total births, Australia, 1971-2020

Source: ABS, National state and territory population (Cat. No. 3101.0); ABS, Australian Historical Population Statistics (Cat. No. 3105.0.65.001)

The impact of COVID-19 on Australian fertility rates is still uncertain. Economic upheavals tend to cause lower fertility rates, with couples and families deferring or abandoning plans to have children. A similar pattern would be expected with the pandemic, as it has resulted in significant job losses and continued concerns about job security for many more, as well as the fear of bringing children into an ‘unsafe’ world. What would be very unexpected is if the months in lockdown, most notably in Victoria, led to an upswing in births!

In the next few articles, we will look at the impact of COVID on interstate migration, metropolitan to regional migration and local area housing market impacts.